Some thoughts on running a screenshot moderation service, one month later

I find content moderation really fascinating, because it's in many ways the locus point of our current social fixation with "cancel culture" as well as online toxicity more generally.

I migrated from Twitter to Mastodon in 2017, but didn't give up Twitter entirely until Elon Musk took it over. At that point I'd spent quite a lot of time on the Fediverse, and really it's where I discovered myself as a queer person; the loose network of queer posters on the platform I'd joined while discovering my identity as a trans woman was absolutely foundational to how I would eventually see myself, my relationships and the world around me. Much like me, the queer users I encountered were fleeing a particular type of social media, one predicated on driving engagement at a cost to all else.

Early Fediverse prioritised accessibility, driven by an empathy so frequently lacking towards people with visual disabilities online, and normalised adding alt text to images. Part of this translated into creating a space that is more tolerable for neurodivergent people, another empathy so desperately missing online, which resulted in many of the platform's social norms around content warnings (CWing selfies with eye contact, for instance). Black, queer and disabled users dared to imagine a better social media, one where expressing joy wasn't an open invitation to abuse, where we could work towards a brighter future without the constant attacks we receive on literally every other platform. Marcia X, Are0h and others established the #fediblock hashtag as the first serious attempt on the platform at community safety, which continues to this day to inform instance administrators about possible unmoderated bad actor instances who've joined the network.

If you came to this essay expecting me to shit all over the moderation approaches on the Fediverse, I'm sorry, this ain't it. The people who moderate Mastodon (et al) servers often do it at great personal cost and as a labour of love, and they do the best they can given imperfect technologies and a lack of resources. I attended the funeral of one recently; I miss talking to her a lot. These people don't deserve so much of the snark they so frequently get...

Mastodon is much more palatable if you think of it as a network of clubs, like on a university campus. You can join as many as you want, and people in clubs talk to people in other clubs, except if a club is known for having a lot of douchebros, which everyone then tries to ignore until said-douchebros decide they're not getting enough attention and then do some bullshit. Each club has its own rules and norms and social histories, and you face being ejected from the club if you act shitty. This is because the people running the club are usually volunteers and don't want to spend more precious time on this earth than necessary dealing with bad behaviour, instead wanting to focus on whatever that club is known for.

This is all annoying and impenetrable if you're a Twitter user wanting to use a service like Twitter that isn't Twitter, but if you're a member of one of those clubs and all of your friends are there, you probably don't see much incentive to add more people to the club, particularly if there's a chance they could end up being one of the aforementioned douchebros. This may translate into a particularly virulent culture of normalising the club's values, so that new members don't cause issues or start undermining the very reasons why everyone likes the club in the first place. When everyone in the club knows the people who make the decisions in the club, there's a lot of pressure on the people who make the decisions not to make decisions that upset the club's membership. Unfortunately, that will simply mean that a club is not right for some people.

Alas, I quite often find myself being "one of those people".

Although I'm queer, I work in journalism, and much of how I understand the world is through that lens. And much like in uni, the only club I ever really connected with was the student newspaper, and all the weird text-loving misfits that sort of place brings.

I've written pretty extensively about why I feel the Fediverse is a challenging place for newsmedia content, but to summarise: lots of people just don't want it there? They'd prefer an experience where they're not constantly being reminded that the government is totally apathetic to their plights as people, and how the world is going to hell in a handbasket a thousand times over, just endlessly endlessly over, which is news they'll see anyway and don't want to consider when posting about embroidery (or whatever)?

Perhaps when you're used to just chatting about life with your friends in the club, a bunch of big accounts running into the room to yell "DOOM! DEATH! MURDER! TRUMP IS OUT TO GET YOU" might not be what people want?

I can definitely empathise.

This results in a culture where political and news discussion is usually hidden behind a content warning, if it's discussed at all. Meanwhile, news orgs by definition are collectives of people who have controversial viewpoints, and that often doesn't translate into being friends with small groups with extremely protective cultures around things like transphobia. My industry right now is going through an intense moral panic around the trans community, which is leading to many titles publishing a lot of content that, to put it politely, might cause some historical regret on behalf of those organisations.

What it means in practice is that orgs tainted in any way by publishing transphobia are not welcome on the Fediverse, which is an admirable moral stance and one I'm fully in support of, except for the fact it basically precludes pretty much the entirety of the British media at this point. For a moderator of a queer Mastodon instance, allowing hostile journalists to expand their platform into a protected space is absolutely a non-starter, which is why instances focused on journalism are frequently defederated, or blocked from interacting with an instance. Journalists on such instances are thus punished for simply sharing a server with other journalists. Is it any wonder, then, that journalism as a profession hasn't migrated to Mastodon in any real capacity? Particularly when, as a profession, we're used to seeing the power we try to hold to account attempt to silence journalists, so we tend to be rather protective of each other as a result?

Good god, I'm 1100 words into this piece and I haven't even talked about XBlock yet. I'm getting to it.

I joined Bluesky both because I was curious about its new approach to doing decentralised microblogging at scale and also because it felt like it was a place where news media could live, that wasn't owned by a single corporate entity like Twitter. I worked with the Financial Times' social media team to establish accounts for my team as well as the broader paper, and those now collectively have over 100,000 followers. I also created the News feed, which is a custom curation of news content automatically generated when verified news orgs publish headlines. Currently, it's the most popular source for news content on the platform.

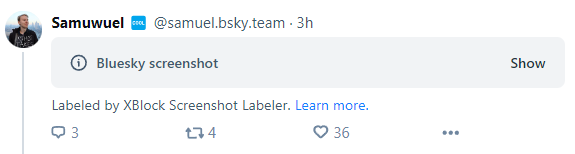

Bluesky doesn't try to be a collection of clubs. It's a proper town square like Twitter was, with so much of that beauty and ugliness intact. Unlike Twitter, however, Bluesky has given users features for navigating the ugliness, with tools striving for the same sort of inclusive, accessible experience that motivated the early Fediverse. Between the way the block button works, the fact communities can subscribe to shared blocklists, and the emergence of 3rd party labeler services, the Bluesky team has given users an incredible array of ways to navigate the deluge of content on the app.

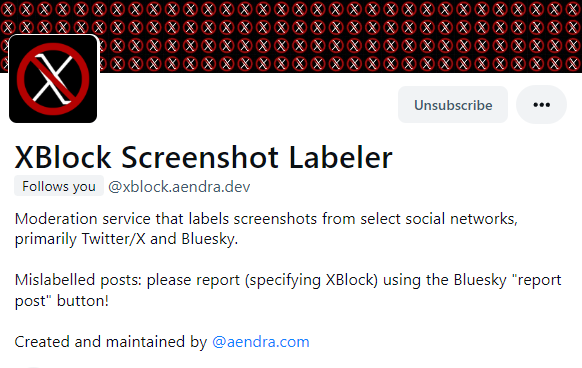

XBlock is the last of these. I followed the 3rd party moderation pull request on the Bluesky GitHub repo for a solid week before it merged, so that I was able to be one of the first users on the platform to deploy a service. I won't claim the idea to create a screenshot moderation service was original; I'd seen people on the platform suggest it a few times (mostly in the form of "somebody please make this"). I mainly wanted to do it as a machine learning project, to see how hard it would be to deploy a model at scale similar to the 1st party labeler that automatically places content warnings on images. It's both been easier and harder than I thought it would be.

To start with how it's been easier, the Ozone content moderation platform is extremely cool (even though I wish the UI was a little bit easier to use on mobile, given I do a lot of moderation from my phone). It's awesome to be able to have an interface that receives reports from users when a post has been mislabelled, and allows me to manually create labels on their behalf. I didn't anticipate such an overwhelming response to XBlock, and although I initially hand-labelled a lot of images when first training the model, at this point most of the training data is either generated by the model itself or derived from user reports. I'm also getting much better speed out of my model than I anticipated, given I'm using the "large" version of google/vit as my base.

What's been harder to deal with is the feeling like I always have a queue of reports to deal with, and if I let it get too big, it will be even harder to dig myself out from under. Meanwhile, I barely have enough executive function to do laundry – I've found staying on top of the queue really challenging as someone with unmedicated ADHD! My dream is that I get the model trained well enough that I only have to respond to a handful of reports a day, and can possibly find a few volunteers to help with triage, but I still have a lot of training and manual annotating to do before I get to that point.

I'm old enough to remember when the Internet wasn't a group of five websites, each consisting of screenshots of text from the other four.

— Tom Eastman (@tveastman) December 3, 2018

What drives me is that I find the concept really fascinating. There's a sentiment, that the Internet at this point is the same five websites taking screenshots of each other, and my experience with XBlock has very much reinforced that feeling for me. Being able to toggle entire portions of the Internet off in your social media experience allows users to dramatically change their experience: You don't see dunks anymore by warning about Twitter posts. You can turn off horny anonymous questions by setting NGL to "hide". Putting Reddit posts behind a CW means you can choose whether you see a lot of news content, and the experimental "News" label will mean that you can hide news media content altogether if it's not something you want to see, or you simply need a mental break from the current news cycle (as someone working in news media, this is an absolute godsend for me). And you can basically turn the volume of Trump posts to nil by hiding posts labelled Alt Right.

These labels are preferences; they're not norms, nor should they be. In no way do I advocate for people to hide every piece of content XBlock labels – there is no broader goal with regards to reducing the platform of accounts on other networks, I simply wanted to give people on Bluesky a way to control their social media experience better. What I hope it does, though, is inspire people to think about what their social media experience could be like, particularly if we get to a place in society where we're not just endlessly talking about how shitty Elon Musk, JK Rowling and Donald Trump are.

We need to be able to dream of a world that's better before we're able to make that world, and building better online spaces, where queer joy isn't drowned out by hateful rhetoric and marginalised voices are allowed to speak, is one of the ways we get there.

-Æ.